Since the 1940s, perfluoralkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have been used in a wide variety of industrial and consumer applications as stain and water-resistant coatings.[1] It is now recognized that exposure to these chemicals may lead to adverse health effects.

PFAS are a large group of man-made fluorinated compounds that repel oil and water – in 2018, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) identified 4,730 PFAS-related CAS numbers.[2] They have a wide variety of applications, including fire-fighting foams, nonstick products, insecticides, and other formulations requiring surfactants.[3]

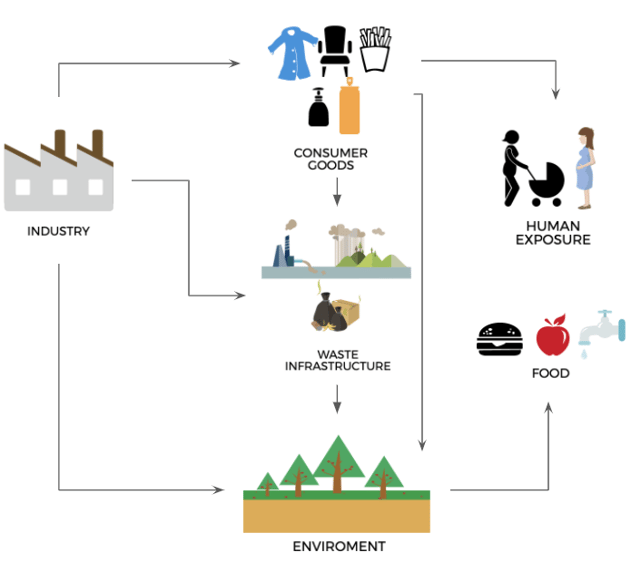

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) definition of PFAS, these substances can be found in:

- Food – when they are packaged in PFAS-containing materials, processed with equipment that use PFAS, or grown in PFAS-contaminated soil or water

- Commercial household products – including stain- and water-repellent fabrics, nonstick products (e.g. Teflon®), polishes, waxes, paints, cleaning products, and fire-fighting foams (a major source of groundwater contamination comes from places where firefighting training occurs)

- Workplaces – including production facilities or industries that use PFAS (e.g. chrome plating, electronics manufacturing, or oil recovery)

- Drinking water – typically localized and associated with a specific facility (e.g. manufacturer, landfill, wastewater treatment plant, firefighter training facility)

- Living organisms – including fish, animals, and humans, where PFAS have the ability to build up and persist over time[4]

The continuous production and use of these chemicals has resulted in the contamination of drinking water sources in several European Union (EU) countries. In many cases, the levels of individual PFAS, such as perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), were found to exceed the limits proposed in the 2018 EU Drinking Water Directive.[5] Methods for treating groundwater are limited to extraction and filtration through granular activated carbon filters.[6]

A key concern relating to PFAS is their extreme persistence in the environment, with shown resistance to most chemical and microbial conventional treatment technologies, and they bioaccumulate in humans and wildlife.

Image Source: Emerging Chemical Risks in Europe

PFAS are absorbed after oral exposure. They then primarily accumulate in the blood serum, kidneys, and liver.[7] Exposure to these chemicals has been shown to adversely affect the immune system and cause low infant birth weights, cancer (for PFOA), and thyroid hormone disruption (for PFOS).[8]

EFSA Publications

In 2008, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) published ‘Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain’ relating to PFOS, PFOA and their salts.[9] This characterized PFAS as environmental pollutants that particularly affect fish and fishery products. It established tolerable daily intakes (TDI) for both PFOS and PFOA and concluded that the general population in the EU were unlikely to suffer negative health effects from daily exposure to these chemicals. It was determined that the indicative dietary exposure for PFOS of 60 ng/kg body weight (BW) per day is below the established TDI of 150 ng/kg BW per day. For PFOA it was determined high-level dietary exposure of 2 and 6 ng/kg BW per day, respectively, are well below the TDI of 1.5 µg/kg BW per day.[10]

In 2010, the EFSA issued a call for data on PFASs in food. This followed a request by the European Commission (EC) to prepare an opinion on the human health risks relating to the presence of these substances in food. Thirteen Member States submitted their analytical results on 27 perfluoroalkylated substances in food, covering the sampling period 1998 to 2012. These results were combined with the findings of a dedicated three-year project conducted by Perfood. Consequently, on March 17, 2010, the EC adopted Recommendation 2010/161/EC on the monitoring of perfluoroalkylated substances in food.[11] The EFSA’s findings were published in a scientific exposure report in 2012, followed by two separate opinions in 2017.

On March 22, 2018, the Scientific Opinion ‘Risk to Human Health Related to the Presence of Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid and Perfluorooctanoic Acid in Food’ was adopted.[12] This covered the risks associated with: Meat and meat products, Eggs and egg products, Milk and dairy products, and Drinking water.

It was determined that although PFOS and PFOA are readily absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract, and excreted in urine and feces, they do not undergo metabolism, with estimated human half-lives of 5 years for PFOS compounds and 2 to 4 years for PFOA.

Based on the human epidemiological studies, the following critical effects were identified:

- PFOS & PFOA – increased cholesterol in serum and reduced birth weights

- PFOS – decreased in vaccination response in children

- PFOA – increased prevalence in high serum levels of the liver enzyme alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

After benchmark modelling of serum levels for these compounds, tolerable weekly intakes (TWIs) were established:

- PFOS – 13 ng/kg BW per week

- PFOA – 6 ng/kg BW per week

It was determined that a considerable proportion of the population in the EU exceeds both TWIs.

2020 – ‘Risk to Human Health Related to the Presence of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Food’

On July 9, 2020, the EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM) adopted its latest scientific opinion. This focused on the assessment of four PFAS: PFOS, PFOA, perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), and perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS).

Based on animal and human studies, it was determined the most critical effects were on the immune system. However, the results of this study differed from the 2018 opinion because, where previously the main critical effect was considered to be increased cholesterol when determining the TWI, it has now been established the primary concern is the decreased response of the immune system to vaccination. The latest opinion also differs from previous studies because it considers combined exposure to multiple chemicals, in accordance with recent guidelines.

The study found that ‘fish meat’, ‘eggs and egg products’, and ‘fruit and fruit products’ contributed most to the exposure. It was also determined that children were the most exposed group, following exposure during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

A TWI of 4.4 ng/kg BW per week was established. This is based on physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling that considers accumulation over time and its correspondence to long-term maternal exposure. This level is estimated to protect children from the observed adverse effects of PFAS exposure. The scientific opinion does, however, include a note of caution that certain parts of the EU’s population are estimated to exceed this threshold.[13]

.png?width=646&name=fpas%20diseases%20(1).png)

Image Source: Emerging Chemical Risks in Europe

PFAS in Food Packaging

The German Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung (BfR) currently lists 12 fluorinated substances that are likely to be used as food packaging materials. At the same time, the US Federal Drug Administration (FDA) lists 28 fluorinated substances to confer grease/oil/water-resistance to food packaging materials.

In September 2020, the OECD published ‘Series on Risk Management No.58 – PFASs and Alternatives in Food Packaging (Paper and Paperboard)’.[14] The document provides insights into market trends and gives policy recommendations developed by the Global Perfluorinated Chemicals (PFC) Group, with addressing two aspects:

- Current use

- Chemical and non-chemical alternatives, and their commercial availability

The report notes that for alternatives, short-chain (SC) PFAS and non-fluorinated alternatives to long-chain (LC) PFAS are suitable for use in paper and paperboard food packaging. These are both commercially available and were found to meet the high repellence specifications required for common food and pet food packaging. In certain applications, it was found that non-fluorinated alternatives had advantages over SC PFAS.

Currently, non-fluorinated alternatives make up approximately around 1% of the market. This is because their adoption would result in an increase of between 11% and 32% in food packaging costs. In addition, there are technical challenges associated with their application.

The OECD’s review provides a number of policy recommendations. These are aimed at both international organizations and the manufacturing industry. In addition, it contains recommendations on future areas of study.

Further Trends

Biomonitoring of blood samples from the EU has detected a variety of PFAS compounds. While there has been a decrease in the presence of the most prevalent PFAS – PFOA and PFOS – there has been an increase in ‘novel’ PFAS.[15]

In the US, PFOA, PFOS, and their related chemicals are no longer manufactured following phase-outs and support from the PFOA Stewardship Program. They can however be imported into the US. [16] Some retailers have taken the initiative to move away from using food contact materials that contain certain PFAS and certain states, such as Washington and Maine, have introduced bans. New York State is currently finalizing its regulation.[17] The FDA has also recently made available test methods to quantify the level of some PFAS in food.[18]

However, there are concerns that too much attention is being given to PFOA and PFOS. It has been pointed out that other substances, such as fluorotelomer alcohols FTOHs and polyfluoroalkyl phosphate esters (PAPs), as well as other chain lengths of the carboxylates and sulfonates PAPs, also need to be monitored.[19]

It is clear that further investigations will lead to a greater understanding of the adverse impacts of PFAS on animal and human health. The EFSA’s 2020 report has already called for studies into the impact of PFNA and PFHxS on the immune system and the effect of PFASs on thyroid hormone levels and neurodevelopment. There will also be studies to characterize the mode of action of immunotoxicity and mammary gland development, assess immune outcomes including risk of infection, alongside experimental studies to understand and quantify the connection between PFASs and blood lipids, and more advanced PBPK models.[20]

It is evident that the food packaging sector is going to continue to receive a considerable amount of attention in relation to its use of PFASs. It can be surmised that, as our understanding grows, an increasing number of markets will introduce restrictions on harmful PFASs. The EFSA’s scientific advice will continue to support risk managers as they work out how best to protect consumers from harmful exposure to PFAS.[21]

[1] Risk to human health related to the presence of perfluoroalkyl substances in food, EFSA, ADOPTED: 9 July 2020 doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2020.6223

[2]https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-12/documents/ffrrofactsheet_contaminants_pfos_pfoa_11-20-17_508_0.pdf

[3]https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/human/chemicals/emerging-chemical-risks-in-europe & https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/chemical_safety/contaminants/catalogue/pfas_en

[4] https://www.epa.gov/pfas/basic-information-pfas

[5] https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/human/chemicals/emerging-chemical-risks-in-europe

[6]https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-12/documents/ffrrofactsheet_contaminants_pfos_pfoa_11-20-17_508_0.pdf

[7]https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2017-12/documents/ffrrofactsheet_contaminants_pfos_pfoa_11-20-17_508_0.pdf

[8] https://www.epa.gov/pfas/basic-information-pfas & https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/human/chemicals/emerging-chemical-risks-in-europe

[9] https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.2903/j.efsa.2008.653

[10] Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Contaminants in the Food chain on Perfluooctane sulfonate (PFOS) perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and their salts. EFSA Journal 2008; Journal number, 653, pp. 1–131 & https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/news/efsa-opinion-two-environmental-pollutants-pfos-and-pfoa-present-food

[11] https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/chemical_safety/contaminants/catalogue/pfas_en & https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32010H0161

[12] https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5194

[13] Risk to human health related to the presence of perfluoroalkyl substances in food, EFSA, ADOPTED: 9 July 2020 doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2020.6223

[14] PFASs and alternatives in food packaging (paper and paperboard): Report on the commercial availability and current uses; Series on Risk Management No. 58

[15] https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/human/chemicals/emerging-chemical-risks-in-europe

[16] https://www.epa.gov/pfas/basic-information-pfas

[17]https://www.foodpackagingforum.org/news/article-on-trending-phase-out-of-pfas-in-food-packaging & https://www.weny.com/story/42407784/ny-legislators-vote-to-ban-pfas-chemicals-in-food-packaging

[18]https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsan-constituent-updates/fda-makes-available-testing-method-pfas-foods-and-final-results-recent-surveys

[19] https://www.foodpackagingforum.org/news/article-on-trending-phase-out-of-pfas-in-food-packaging & https://www.technologynetworks.com/applied-sciences/articles/harmful-pfas-only-come-from-old-food-packaging-right-wrong-333426

[20] https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.2903/j.efsa.2020.6223

[21] https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/news/pfas-food-efsa-assesses-risks-and-sets-tolerable-intake

.webp?width=1644&height=1254&name=Food%20Safety%20Dashboard%201%20(1).webp)