Foreign object contamination — from plastic shards to metal fragments — is no longer rare. Over the past three years, SGS Digicomply has recorded a threefold increase in such incidents globally. What’s driving this surge, and why are so many contaminated products still reaching consumers?

In this article, we break down the latest data, explore the root causes behind the spike, and outline what the food industry must do to respond.

What Are Foreign Object Contaminations?

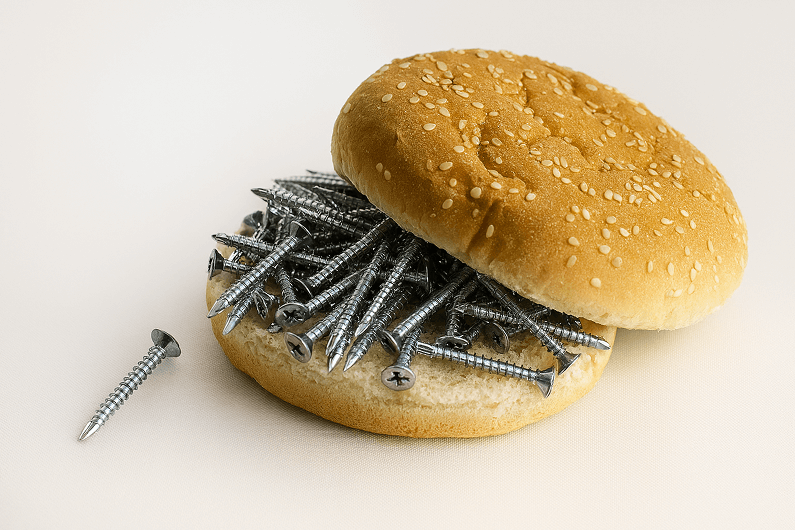

Foreign object incidents refer to the unintended presence of physical materials in food products — typically plastic, metal, wood, rubber, bone, or glass. These are not chemical residues or pathogens, but solid contaminants that often result in visible hazards: chipped teeth, choking, or internal injuries.

Unlike microbial contamination, which may remain invisible and require testing, physical contaminants are immediately tangible. A consumer biting into a piece of metal doesn’t need lab results — they need a dentist.

Regulators around the world classify such incidents as high-risk. In the U.S., they typically trigger Class I or II recalls. In the EU, they are treated as violations of GMP, HACCP, and — often — consumer safety laws under the General Food Law Regulation.

And while the food industry has invested heavily in microbial testing and allergen management, physical hazard controls — often considered more “basic” — are lagging behind.

The Data: A Surge Too Big to Ignore

SGS Digicomply data shows a sharp escalation in foreign object incidents over the past five years. Starting in 2018, reports steadily increased — but in 2024, the curve steepened dramatically, peaking at over 700 incidents reported by government bodies globally.

.png?width=570&height=260&name=Mentions%20of%20Foreign%20Object-Related%20Incidents%20(2010%E2%80%932025).png)

This insight has been timely identified and is available to users through the SGS Digicomply Food Safety Intelligence Hub. Feel free to explore the Food Safety Intelligence Hub demo and try this tool in action.

The vast majority of these cases result in full product recalls, with only a small portion detected through internal controls or consumer complaints — a clear indication that many contaminated products are still reaching the market.

The trend spans multiple product categories, with meat, fruits and vegetables, prepared foods, and bakery items among the most frequently affected. Geographically, the issue is widespread, with the highest number of incidents reported across both Europe and North America. Countries like Germany, the United States, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands are consistently among the top sources of reported cases, underscoring the global nature of the problem.

So What’s Causing the Spike?

The rise in foreign object contamination isn’t random — it reflects deeper, structural weaknesses in the way modern food is produced, inspected, and distributed. Several converging factors are driving this trend.

One of the most significant is aging equipment. In many food production facilities, machinery is running beyond its intended lifecycle. Worn conveyor belts, cracked plastic components, loose screws — all of these can easily find their way into a production line, especially under high-speed, high-volume conditions. While metal detectors are widely used, they often fail to detect non-metallic materials like wood, rubber, or soft plastic.

Another factor is workforce instability. Since the pandemic, many producers have faced chronic staff turnover and labor shortages. Temporary workers and undertrained staff may be unaware of how small maintenance lapses — like using an old cleaning brush or skipping a visual inspection — can lead to serious contamination risks.

Supply chain complexity also plays a role. Today’s food products often include components from dozens of different suppliers. A minor packaging failure or equipment issue at one supplier can contaminate ingredients that pass through multiple hands before reaching the final product. By the time the foreign object is discovered, it may be embedded in hundreds of units across several markets.

Finally, there’s a technological gap. Many plants still rely on detection systems that aren’t calibrated to pick up diverse object types. Glass, wood, and plastic are easily missed unless advanced X-ray or optical systems are in place — and even then, poor calibration or inconsistent usage can leave blind spots.

What Needs to Change

The current wave of foreign object incidents isn’t just a series of isolated mistakes — it reflects a broader gap in how food businesses assess and manage physical risks. Addressing it requires more than upgrading detection systems. It demands a mindset shift.

First, companies need to reassess whether their hazard analysis processes truly reflect current realities. Many HACCP plans treat physical contamination as a basic, low-probability risk — yet real-world data now suggests it’s among the most common causes of recalls. That disconnect needs to be closed.

Second, upstream visibility must improve. Businesses should go beyond supplier self-assessments and introduce targeted audits focused specifically on foreign object prevention — from equipment condition to cleaning tool management. It’s no longer enough to assume supplier compliance; it must be verified.

Third, detection systems must evolve. Metal detectors are foundational, but they don’t catch everything. For high-risk lines — especially those involving rework, manual handling, or fragile packaging — companies should explore X-ray, vision systems, and inline cameras to identify a wider range of contaminants.

Finally, incident response protocols should be stress-tested. How quickly can your team investigate a physical contamination claim? Can you isolate the batch, trace the source, and communicate with authorities within hours, not days? The faster the response, the smaller the damage — to both consumers and brand reputation.

This isn’t just about compliance. It’s about credibility. In a world of rising expectations and real-time scrutiny, physical integrity is the new frontier of food safety.

.webp?width=1644&height=1254&name=Food%20Safety%20Dashboard%201%20(1).webp)